Political Psychology Lesson # 2 - Why we vote defensively

The human mind is funny and fascinating. We are designed with systematic biases for specific purposes. Usually these biases actually work in our favour but often the errors that they cause can be significant and when I say errors, I'm not just talking about occasional goofs, these are predictable patterns of error. Something Dan Ariely calls being "predictably irrational".

In today's post I want to talk about a strong bias that we all have which is often called the "loss aversion" bias. The principle here is that we weigh potential losses as more severe than an equal amount of potential gain. We are more afraid of potential suffering than we are excited about potential pleasure. An example would be someone who invests in a low-risk guaranteed return rather than a higher risk but higher return investment. When we lose $100 it hurts about twice as much as winning $100 feels good.

What does this have to do with politics? Political parties know that to mobilize their voting base, they need to tap into this bias by striking fear. We complain about how parties focus more on slinging mud at their opponents than touting their own plan. It's actually smart psychology. If I can get you to believe that the world will end if my opponent wins, then you'll be more motivated to vote for me than you would if I just focused on what you could gain from me winning.

Once you understand the mechanics of this bias though, it makes you smarten up a little. Negative ads are meant to hack the frailties of the human brain and they are often elaborations, confabulations, and misrepresentations. Their intent is to take advantage of your psychology for someone else's gain. It's the way the game is played, I guess, so that's fine, but I choose to ignore it. I want to make sure that my decisions are based on the best possible interpretation of my opponent's argument. We sometimes call this 'steel-manning' as opposed to a 'straw-man argument' which is where you take the worst possible interpretation of an argument and make that your target.

In a debate over the Carbon Tax in Alberta for example, you could argue for the tax with a "straw-man" approach by saying that anyone who is against the tax is a science denying, short-sighted greedy capitalist. A straw-man against a Carbon Tax in Alberta would be that anyone who is for it is a naive alarmist and environmental extremist.

In contrast, a 'steel-man' argument in favour of the carbon tax would be that pollution costs us in more ways than just carbon emissions. 7 million people die every year because of air pollution (in the world, not in Alberta just for the record). Economists call things like this 'externalities' which means that they are expenses on the public that are not paid for. Making the offender pay for externalities is good policy. It's like charging smokers in advance for the burden they put on the health care system. There's also the issue that if Alberta were to scrap their CTax the federal government's version of it would kick in and all that money would funnel its way to Ottawa instead. Nobody wants that. Sure you could fight it legally but that would likely be expensive an fruitless.

A 'steel-man' against the carbon tax is that the best case scenario, if every nation in the world taxed their carbon, some estimates are that we would lower global temperatures by about 2 degrees 100 years from now. Those differences are three generations away and negligible. Research out of B.C. shows that their carbon tax has barely reduced their carbon emissions at all. I suspect it has been the same in Alberta. If we were really serious about reducing carbon we would strongly consider nuclear (perhaps not in Alberta but in other parts of Canada and the world). Nuclear power is cheap and greener than renewables. Wind and solar are getting cheaper and more efficient but still are not reliable enough to replace fossil fuels. Our demand cannot be met by renewables. Not yet anyway.

So given the best possible interpretations of either argument, I feel like it is reasonable to remove the Carbon Tax from burdening homes, farms, and other non-profits. If we're going to put a price on pollution it should go to the biggest polluters so that they are incentivized to reduce their emissions. Heating our homes and fueling our vehicles is already expensive, there is enough incentive to reduce our footprint without an extra tax. Meanwhile, we continue to invest in research and development so that we can find cleaner and cheaper energy sources like geothermal, LNG, and maybe even nuclear, as well as tapping into our wind and solar resources. Let's keep an open mind about it.

I digress.

When you take an issue like the carbon tax that is nuanced and complicated (far beyond my knowledge on the matter) it can be easy just to resort to a simple straw-man attack and focus on what people will lose if they don't vote for you. ie. "If you don't vote for me we'll all be under water in ten years." or "If you don't vote for me the economy will entirely collapse because gasoline is 7 cents more expensive."

If you hear those arguments, you're getting played.

I hope to not use these tactics myself but I'm human and I might go there. Please call me on it.

Here's my view on this Alberta election though. I'm not afraid of Jason Kenney winning and I'm not afraid of Rachel Notley winning. The world will continue to turn either way.

That being said, I don't believe that either of their plans are what's best for the province. We're currently paying for today by borrowing from tomorrow and it's getting worse. Reducing taxes and reducing funding to social programs is a gamble that I don't think will work either.

I believe in Stephen Mandel and the Alberta Party's vision to add jobs and grow the economy so we can pay down our debt and invest in our kids. You're free to believe otherwise but make sure your belief isn't skewed by the loss aversion bias.

In today's post I want to talk about a strong bias that we all have which is often called the "loss aversion" bias. The principle here is that we weigh potential losses as more severe than an equal amount of potential gain. We are more afraid of potential suffering than we are excited about potential pleasure. An example would be someone who invests in a low-risk guaranteed return rather than a higher risk but higher return investment. When we lose $100 it hurts about twice as much as winning $100 feels good.

What does this have to do with politics? Political parties know that to mobilize their voting base, they need to tap into this bias by striking fear. We complain about how parties focus more on slinging mud at their opponents than touting their own plan. It's actually smart psychology. If I can get you to believe that the world will end if my opponent wins, then you'll be more motivated to vote for me than you would if I just focused on what you could gain from me winning.

Once you understand the mechanics of this bias though, it makes you smarten up a little. Negative ads are meant to hack the frailties of the human brain and they are often elaborations, confabulations, and misrepresentations. Their intent is to take advantage of your psychology for someone else's gain. It's the way the game is played, I guess, so that's fine, but I choose to ignore it. I want to make sure that my decisions are based on the best possible interpretation of my opponent's argument. We sometimes call this 'steel-manning' as opposed to a 'straw-man argument' which is where you take the worst possible interpretation of an argument and make that your target.

In a debate over the Carbon Tax in Alberta for example, you could argue for the tax with a "straw-man" approach by saying that anyone who is against the tax is a science denying, short-sighted greedy capitalist. A straw-man against a Carbon Tax in Alberta would be that anyone who is for it is a naive alarmist and environmental extremist.

In contrast, a 'steel-man' argument in favour of the carbon tax would be that pollution costs us in more ways than just carbon emissions. 7 million people die every year because of air pollution (in the world, not in Alberta just for the record). Economists call things like this 'externalities' which means that they are expenses on the public that are not paid for. Making the offender pay for externalities is good policy. It's like charging smokers in advance for the burden they put on the health care system. There's also the issue that if Alberta were to scrap their CTax the federal government's version of it would kick in and all that money would funnel its way to Ottawa instead. Nobody wants that. Sure you could fight it legally but that would likely be expensive an fruitless.

A 'steel-man' against the carbon tax is that the best case scenario, if every nation in the world taxed their carbon, some estimates are that we would lower global temperatures by about 2 degrees 100 years from now. Those differences are three generations away and negligible. Research out of B.C. shows that their carbon tax has barely reduced their carbon emissions at all. I suspect it has been the same in Alberta. If we were really serious about reducing carbon we would strongly consider nuclear (perhaps not in Alberta but in other parts of Canada and the world). Nuclear power is cheap and greener than renewables. Wind and solar are getting cheaper and more efficient but still are not reliable enough to replace fossil fuels. Our demand cannot be met by renewables. Not yet anyway.

So given the best possible interpretations of either argument, I feel like it is reasonable to remove the Carbon Tax from burdening homes, farms, and other non-profits. If we're going to put a price on pollution it should go to the biggest polluters so that they are incentivized to reduce their emissions. Heating our homes and fueling our vehicles is already expensive, there is enough incentive to reduce our footprint without an extra tax. Meanwhile, we continue to invest in research and development so that we can find cleaner and cheaper energy sources like geothermal, LNG, and maybe even nuclear, as well as tapping into our wind and solar resources. Let's keep an open mind about it.

I digress.

When you take an issue like the carbon tax that is nuanced and complicated (far beyond my knowledge on the matter) it can be easy just to resort to a simple straw-man attack and focus on what people will lose if they don't vote for you. ie. "If you don't vote for me we'll all be under water in ten years." or "If you don't vote for me the economy will entirely collapse because gasoline is 7 cents more expensive."

If you hear those arguments, you're getting played.

I hope to not use these tactics myself but I'm human and I might go there. Please call me on it.

Here's my view on this Alberta election though. I'm not afraid of Jason Kenney winning and I'm not afraid of Rachel Notley winning. The world will continue to turn either way.

That being said, I don't believe that either of their plans are what's best for the province. We're currently paying for today by borrowing from tomorrow and it's getting worse. Reducing taxes and reducing funding to social programs is a gamble that I don't think will work either.

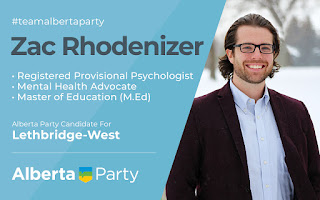

I believe in Stephen Mandel and the Alberta Party's vision to add jobs and grow the economy so we can pay down our debt and invest in our kids. You're free to believe otherwise but make sure your belief isn't skewed by the loss aversion bias.

Comments

Post a Comment